WOLFGANG

my older brother

What does the reader think about reconciliation = Wiedergutmachung?

Should I feel guilty about what my parents experienced?

Instead of judging, should I research and take into account what actually happened?

Three adult men, including my father, expected to be financially secure in a business that could not be successful enough any more after the war. My brother tried to avoid bankruptcy by creating two more branches selling Thust monuments, one after the fall of the wall near Leipzig, the other in Wroclaw, Breslau, his birthplace.

I now know that his tour through Silesia with 150 invited guests was THE END of his and his, our family’s work after 200 years.

After my brother’s death every member of his family made sure not to pay parts of his debts. It was a drag for us living in England and others living in Paris, and to affect his two adopted children and their 3 children, his grandchildren, as well…

He represents an important part of OUR FAMILY, a disjointed entity, a growing success story and a sudden complete destruction in the years of 1945 – 46, a lingering after the war, a feeling of homesickness in my father’s families and a brave effort to overcome my mothers own illness and disappointments I now do understand why I kept my distance, even cried at one wedding gathering. I felt desperate about any gloss, pomp, pride or joy within any family gathering then.

I admit, I still feel like a joy-killer because of it. And I should not be, because there is no reason now to be a downer.

But it is just the same when I am confronted with British Royal Family celebrations. I know about the joy but I can not share it.

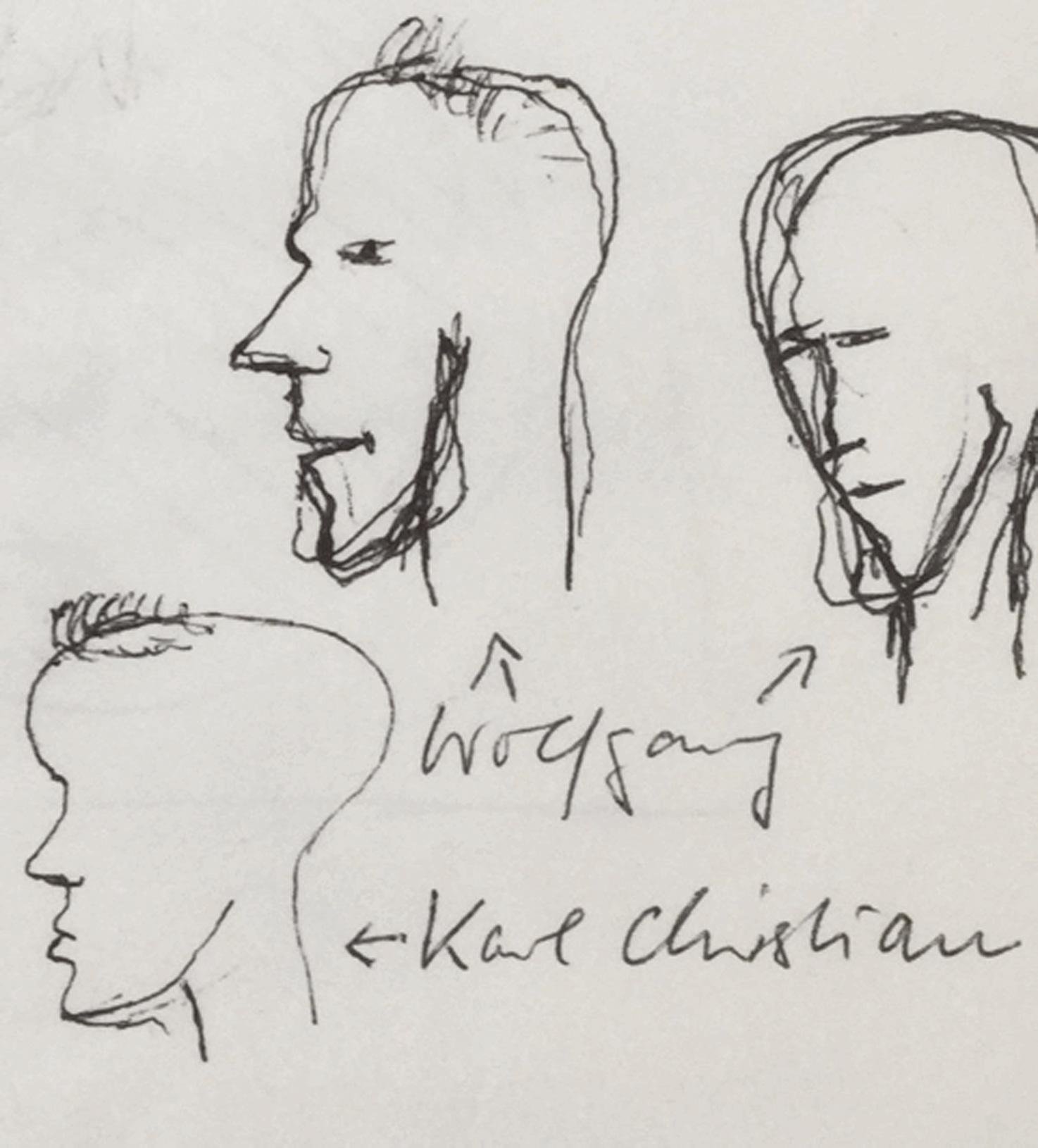

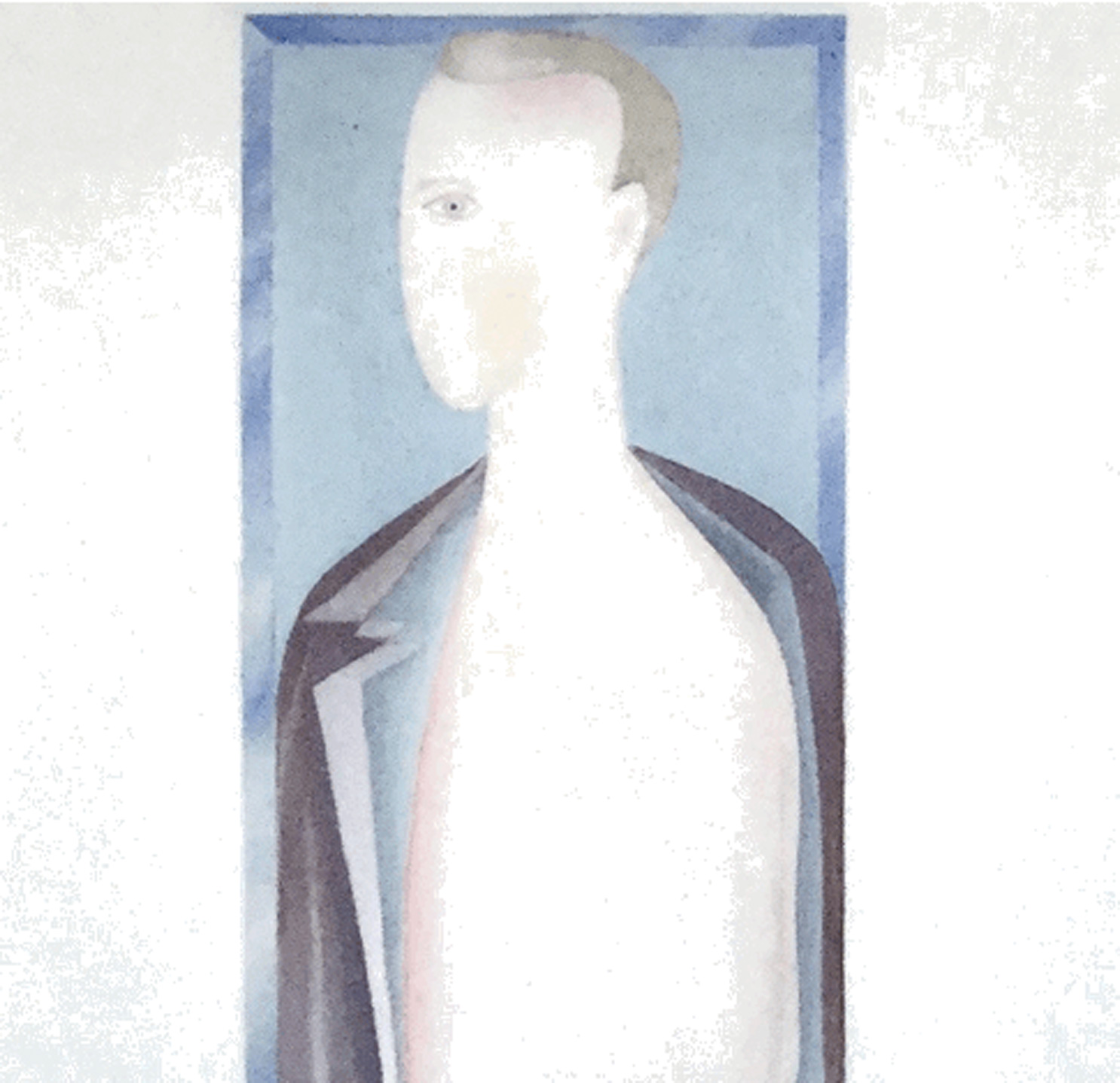

I kept sketches of my older brother and a portrait I painted in 1968. My brother died in 2021.

I took a snapshot of him in 2019.

I am glad to have these two portraits, the painting and the photo of him, they are telling.

Do I need memories like that ? Do I need additional stories ?

Does he deserve special attention within “THE FAMILY”?

I chose him because of the unavoidable bond between us. He was 4 years older and I looked up to HIM,

– not in the same way to my one year younger brother.

We 3 lived together in one room for 7 years, after 1945, in two different beds, the first one bigger than the second one in size. My brother was 9 when we escaped from the Russians. The journey affected us, but him more than me. After our escape he often woke us up screaming fire, fire. And I also woke up at nights. I didn’t dare to go to the loo, in fear of darkness.

I shook my head noisily until a glimmer of light made me feel secure.

Somehow I felt my brother was odd, loud and not that clever but there was a fatherly distance between him and me. He was the top builder, (the Baumeister), I had my own ideas. I was chatty, my mother said, but shy to people outside the family. Silently I had my imagined girlfriend named Memmie.

Everybody laughed.

2017

Dear Wolfgang,

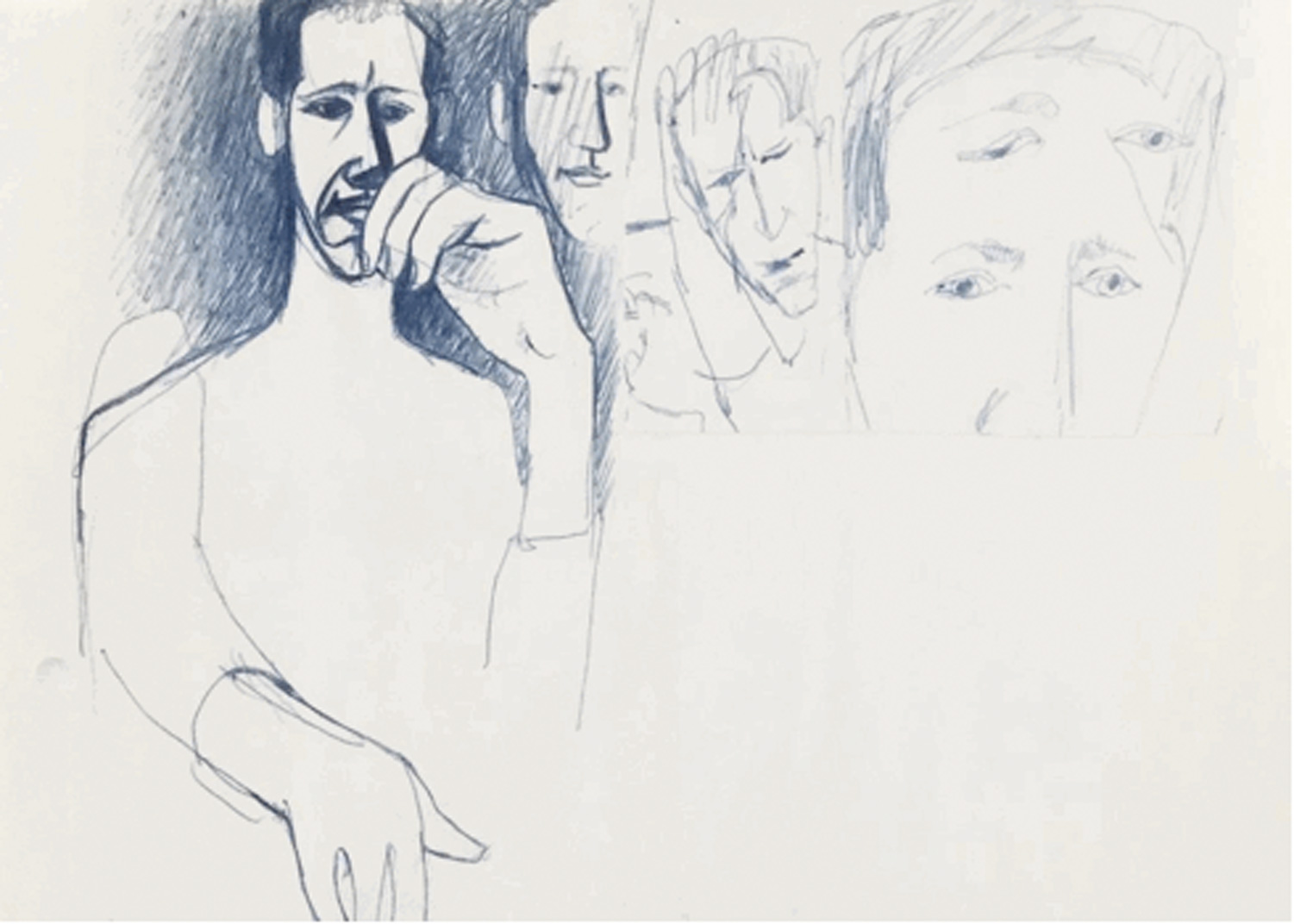

It was 1968 that I drew you. You weren’t sitting down, you were active,

always four steps ahead of me since our youth. Back then, I was planning to paint a portrait for the first time, one that was more of a cross-section, not just of what we are physically

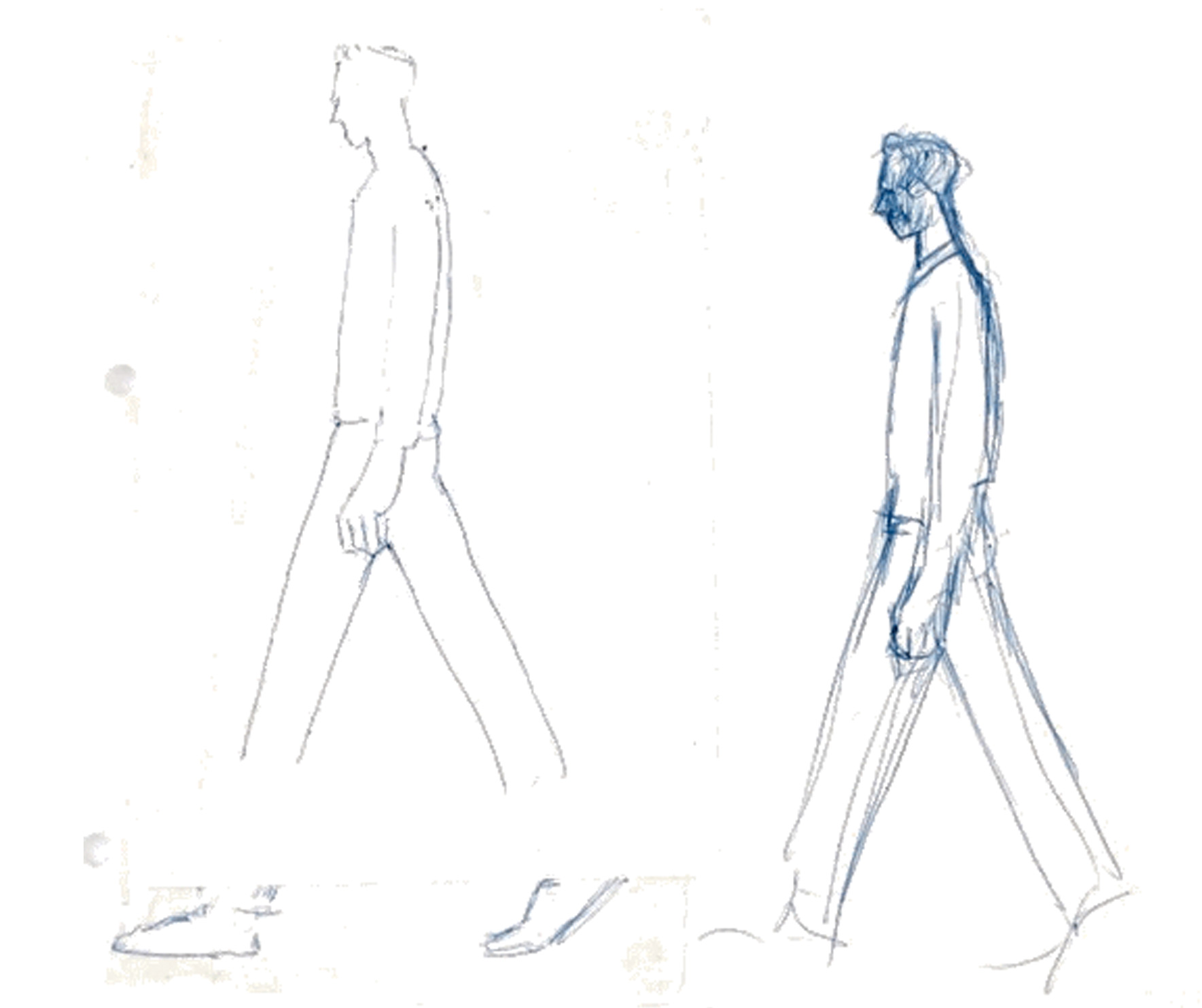

and what we wear, but also of how we deal with the outside world. You were a young businessman who confidently moved forward – even against all expectations.

In my picture, you are running against the current – but also open and vulnerable.

I now found my sketches again and, amazingly, also the picture that I painted in the first year of my marriage in Moselweiß near Koblenz. You didn’t like it, but it says something

about our relationship to each other, my observations of my older brother

and your judgments of me. I tried to understand you with the means at my disposal.

Please don’t look over my shoulder until I have results that I also agree with.

I am forever unsure

Your Wilfried

In 1968 I drew my older brother in when he had decided to work in the “FIRMA”, the family business that he felt obliged to save from bankruptcy.

I did these sketches for my painting of him.

In 2019 I took a snapshot of him on my iPhone, in the workshop where our great-grandfather founded the company Thust, 200 years ago, in 1819.

My painting did show the forward looking young man then in 1968. My photos 50 years later reveal moments of his ‘fulfilments’, although as I show he had to sit on a chair because of his back. He avoided operations because, as he said, his business didn’t allow him any time for that and the time a cure needed after that. He cancelled these operations 3 times, the day before.

Worries about his debts caused his death. Nobody could stop him. He died in 2022 – two years later.

I carefully planned the painting I did of him in 1968. It shows him entering his life as a young wilful business man. His clothes were like layers to support his performance. His body was like his inner life, open to development, not open to me and others. It always fascinated me to deal with layers and I tried to represent in that way an inner and outer existence, the inner being the hidden and less obvious areas, and I even think about that within myself.

When I was 15 I was keen to create an inside of my models. This got me to the thoughts on the painting about my brother. In the 1990s I went to an exhibition of the American painter Hopper and liked what I saw because he seem to look into houses from the outside in. Hitchcock’s films do the same.

My brother invited me with 150 other guests to a celebration of the 200 years history of the business THUST in Silesia.

He paid for the hotel, including all amenities and food in Breslau (today named Wroclaw), the town he was born in and where our father received his doctorate in Geology in the famous town hall that miraculously survived all distractions around it.

From there he organised a tour to the north along the River Oder and to the border of Czechoslovakia where the quarries of the Thust factory had been and still operating to an extend even now.

On the way he communicated with the mayor of the place where the founder had lived and worked in 1819 called Pilawa Gorab, Gnadenfrei, meaning being blessed. It was a Lutheran congregation.

Every grave had the same sized stone plate on the ground because we are all equal before god.

My brother was well received in the village hall and then let to the workshop, still in use.

And that is where I took the chance to use my iphone.

Here I come back to my thoughts on families. I feel right to have chosen my brother in my art, as the centre of my own family experience. It makes me authentic and nearer to a true story that I can share with others.

On the journey to Poland with him I found time to talk one night as we had to share a bed and I revealed that I always felt alienated by family gatherings. He was quite shocked. I added that I could not understand why nobody ever asked me anything about my divorce as if that was “normal” to happen. He took it in. Days later he told me that in retrospect he had made the wrong decision to marry his wife and that at the time he was too shy to come out to the woman he really loved. It was very moving to me to hear this.

After my brother’s death – two years later – his wife told me that she could not relate to him for quite some years and that she felt relieved when he had gone. I sort of knew. I wasn’t even shocked, nobody was, I think.

I have certainly pictures that show that this was NOT always so between them at all but the bond didn’t last. Why ?

My brother had followed his own mission, spending years mostly in his car to manage all contacts and deals whilst driving as a “salesman” in order to release his burdens of debts he had accumulated over the years. As he refused operations on his back on my journey with him I had to witness his downfall, literally. He could hardly walk and later on needed a wheelchair. Living in his own “capsule” brought him down.

Tragic it may be, but HE never saw it like that. And, when I listened to many people who had dealings with him they all were full of praise about his vitality, friendly open approach, care for his workforce and about his sense for a respectful representation of the dead in burials and the fine art of masonry that often he chose and designed himself.

For me it is important to judge him rightly.

This is the place where my grandfather’s family lived peacefully. You can see the quarries and the factory on the right.

The factory was always part of this village that was half German (now Polish), half Chekslovakian.

We went to see my grandfather’s place. His grave had to be dug secretly, near ‘his’ factory on the side of a forest in 1946. His memorial stone was brought in by my brother because of EU rules in the 1980s

I made a painting in 2016, a turning table where the visitor could shift and change the outlines of Europe’s uncertain borders. That is my almost silly comment on the confusion of political divides in Europe, often completely disregarding human relevance. I don’t belittle the dramatic and violent circumstances that happened. But what I ridicule is the glorification of the successes of war. I am interested in case studies that explain why wars happen and any steps to avoid them.

E U R O P E ?

Germany before Hitler’s invasions. Poland now, including Silesia

I am interested in the historical and political facts of our family and recognise the successes my brother felt to be part of. He pointed at the process of ‘Wiedergutmachung’ = reconciliation after the 2WW and through the EU. I admit that I was astonished about the housing and living standards NOW in Poland.

He represents an important part of OUR FAMILY, a disjointed entity, a growing success story and a sudden complete destruction in the years of 1945 – 46, a lingering after the war, a feeling of homesickness in my father’s families and a brave effort by my mother to overcome her own illness and disappointments. I now do understand why I kept my distance, even cried at one wedding gathering. I felt desperate about any gloss, pomp, pride or joy within any family gathering then.

I admit, I still feel like a joy killer, because of it. And I should not be, because there is no reason now to be a downer. But it is just the same when I am confronted with British Royal Family celebrations. I know about the joy but I can not share it.

The following pictures show my brother still even here on our journey negotiating a deal with the woman running the workforce consisting of a few men.

My Father

on his escape in 1946

Nobody really knew when and how to follow orders to leave Silesia. My grandfather stayed on. He left his very carefully and cautiously written diary reporting how he attempted to help people and his family to overcome the uncertainties, after his wife and some relatives had already moved to the West.

He called for my father to help him in dealing with skirmishing men looking for goods everywhere to sell. On one of those occasions my father saved his nice from being raped. But after that day he was taken by a car at night to an internment camp with ‘beds’ arranged like in Auschwitz. Nobody knew where he was. Although he worked out that he was at the industrial end of Silesia, he couldn’t contact his father. As a geologist, though, and through his interest in the geography of this land, he worked it out. He attracted attention to help in the kitchen to make soups and, also under guard, led groups in collecting herbs etc. He planned it carefully and wasn’t discovered by the guards or dogs to escape. After that he spent four months hiding in forests, occasionally coming out as a mushroom dealer…

In 1971 he had to undergo a minor hernia surgery, but three times during the nights he left the hospital unnoticed… and died.

Two things mark him out: In the 1920s he created yearly a booklet FROM STONES TO BREAD, ‘Aus Steinen Brot’, representing the workforce and including their point of view. After the war, he worked on changes in the so-called Cemetery culture and supported the use of white stones. For me he himself became a kind of monument. His intentions spoiled by the Nazis BLOOD and SOIL = Blut und Boden movement.

Here you see my father in a meeting with representatives of ‘Friedhof und Denkmal’ an organisation concerned about good monuments. These people were also often Thust clients and chose stones of huge collections of work done by different stonemasons